Postcolonial history

Bern travelers sought their salvation in Africa – with fatal consequences

In his PhD thesis, Tevodai Mambai investigates how and why well-known Bern travelers such as René Gardi and Charlotte von Graffenried painted a derogatory and at the same time idealizing picture of his people – and finds long-lost sacred Mafa artifacts in Swiss museums.

I was born in Mokolo in 1981, as one of the Mafa people who are based in the mountains of North Cameroon and Northeast Nigeria. I am part of the larger group of the Vavi, the peasants and farmers. The Biy, the chief of the tribe, is chosen from their midsts. The smaller group of my people are called the Gwalda. In this group, the men turn ore into iron and the women work as potters, healers and midwives.

“Barbaric and wild”, “natural and modest”

The subject I am writing about here will no doubt sound familiar to quite a few of the readers: During a period of around six decades, basically between 1940-2000, around twenty Swiss citizens with a range of backgrounds and professions – missionaries, movie makers, authors and ethnographers – traveled through Mafa country and conveyed a lasting image of my ethnicity to the German-speaking audience. In their travelogues, movies, missionary reports and ethnographic works, they painted a controversial picture of the Mafa – at times barbaric and wild, at others untainted, natural and modest. Their reports from “unknown” Africa were of great interest to the Swiss audience.

My ancestors willingly shared their daily lives with the travelers from Switzerland, they helped them find their way round, they answered their questions. But they knew nothing of the picture these Swiss citizens painted after their encounters and then disseminated.

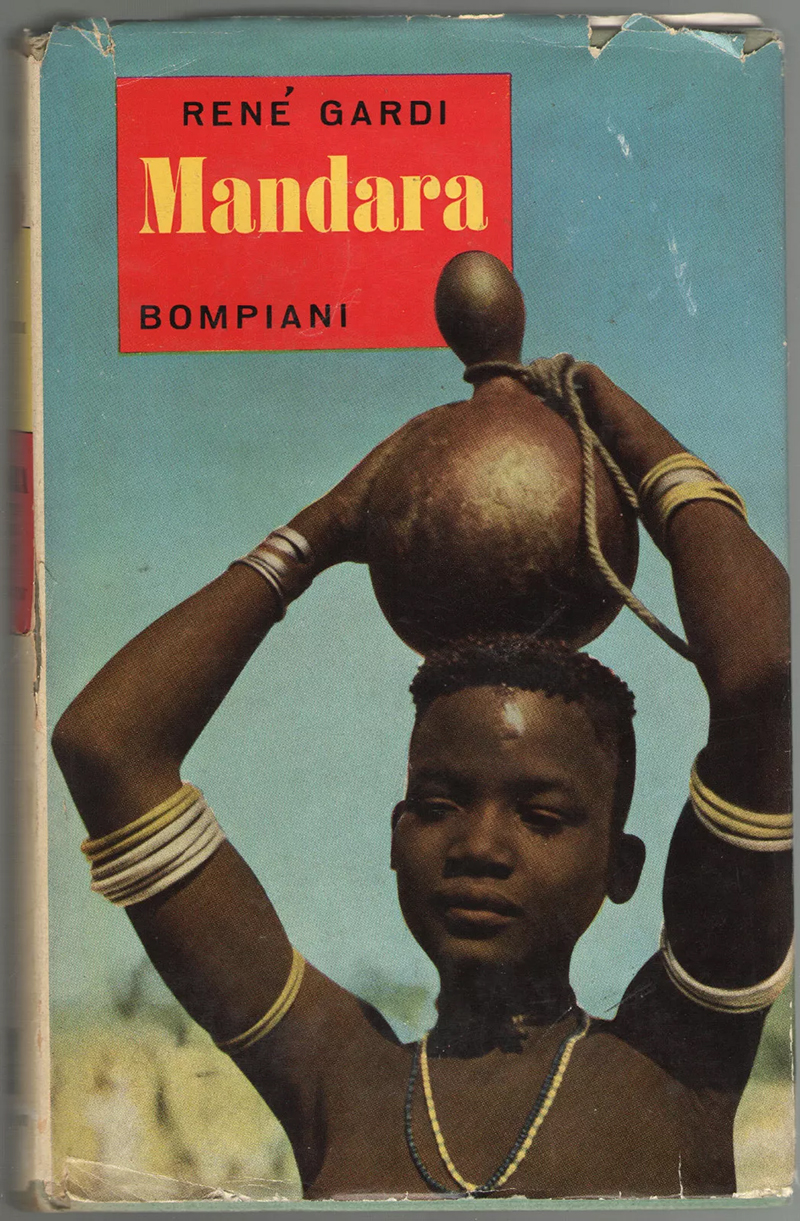

Discovery on the market square

It was not until 1994 on the market square in Mokolo that I came across the picture that was and still is being spread about us in Switzerland. I was just 13 years old at the time and still attending primary school when a photo on a book cover I found in the bookstore of an acquaintance of mine, Pierre Ndoumai, caught my eye: a pretty girl, obviously from my area, with a basket on her head. But I couldn’t find out anything about the content because the book, entitled Mandara, was too expensive for me and was written in German.

Studying German to get the picture straight

When I started studying philosophy, I came across the book again in the Centre Culturelle Français in Cameroon’s capital Yaoundé in 2003. Thanks to Alfred Tanadi, a fellow student and grandson of Daniel Kiligai, who had worked for the Swiss travelers for decades as an assistant and interpreter, I was also able to watch the movie made from the book Mandara from 1959. It triggered very ambivalent feelings in me. So I then decided, in 2005, to stop studying philosophy and start studying German philology to find out more about the travel writer René Gardi, Mandara and other Swiss travelers.

It is a fact that we Mafa feel robbed of our culture: Colonialism, Christianization, school lessons in the language of the former colonial rulers about their history and culture, leave a permanent mark. It was against this backdrop that I co-founded the cultural association Ditsuma, which has as its motto “in deh a ma, a nga ngide diy-tsum nga – honor tradition and look for progress”. As the younger generations of the Mafa, we are dependent on older people for information about particular aspects of our culture.

Something my acquaintance Douva said in one of these discussions in 2010 made me sit up and listen: “A diy Mossieur Duc, nassara hiy ta shike te virziy gay, a ta tsokol skwiy diy tsum nga kumba. Aman skwiy dzham, a skwiy baba a je teva’a. Mejeb ta in lbaa a vena.” Which translates to English as: “It was in the era of Duc (author’s note: French colonial officer who ruled as Chef de Subdivision in Mokolo in the 1950s) that the whites took away our cultural objects. These included ritual and sacred artifacts. The souls of our ancestors have a connection with them.” It goes without saying that this statement irritated me, but at the same time inspired me to search for traces of these objects in Switzerland.

Nine hundred artifacts found in a Swiss museum

In 2015, I had my first mail contact with the Museum der Kulturen Basel (MKB) and one year later I was able to travel to Switzerland. Until this point in time, my picture of Switzerland had been one of red Swiss army knives and Nestlé milk out of a small can. I shared the cost of my flight with the cultural association. My stays in Switzerland, both then and now, gave and are giving me the opportunity to discover that there are around 900 Mafa artifacts in the Museum der Kulturen Basel, in the Bern Historical Museum and in the Burgdorf Castle Museum: weapons, musical instruments, furniture, vessels, ritual and sacred artifacts. The most important collectors were the ethnologist Paul Hinderling and René Gardi. I have now been entrusted with the task of reappraising these Mafa cultural assets in the MKB.

During my appraisal of the Mafa collection, I came across two of the artifacts my acquaintance told me about: the vri (soul jars) and ged pats (head sun, personal spirit) which are seen as ritual artifacts. Bernhard Gardi, son of René Gardi, says his father ordered these vri from Waidam, a potter in Mokolo. But the ged pats still show traces of blood. These are culturally sensitive objects that nobody would give away voluntarily. Anyone giving them away or selling them would have to face the wrath of the spirits and ancestors.

I met Paul Hinderling in 2016 in Saarbrücken together with Isabella Bozsa, at the time curator ad interim for the Africa section at the MKB, to find out more about how these objects were obtained. But I wasn’t able to get any satisfactory response due to his age – he was 92.

Betrayed trust

Today, as a Mafa, I can see that some Swiss travelers abused the trust and the open friendliness of the Mafa, especially since they were in the service of a racist and colonial ideology and self-representation. Genuine pioneers were Gertrud and Hans Eichenberger, a Bernese missionary married couple I had met as an adolescent. They settled in Souledé, not far from Mokolo, in 1948 and then set up their mission. They were members of the Swiss branch of the United Sudan Mission. They came with the alleged motivation to ‘rescue’ the Mafa, to bring them salvation. Gertrud worked in a small medical center, while Hans was a preacher and teacher. Gertrud and Hans were important contacts for other Swiss travelers. In 1949, they were joined by another married couple from Bern, Mirjam and Gottfried Wildermuth-Holzer. They spent two consecutive stays in the village of Souledé. In 1953, the Bern traveler and author René Gardi visited our parents. With Gardi on his journey was Paul Hinderling, from Solothurn. Their three-month ethnographic research focused in particular on the Mafa and their iron production and pottery.

The contact with Hinderling also made it possible for me to find out about Charlotte von Graffenried in 2016. As part of her field research during the 1970s and 80s, she spent a total of 15 months with the peasants and farmers in our mountains. I did not know them personally but met their son, the photographer Michael von Graffenried, who had also visited us several times, in 2022 in Bern.

Bernese motives: marital woes, discrimination, condemnation for pedophilia

I can’t list all the Swiss citizens or Bernese travelers here but when I take a closer look at their biographies and travelogues, I find that their motivation for traveling is no different from that of young Africans traveling to Europe today: The reasons are not just curiosity and an urge to explore but often also dissatisfaction with their everyday lives, social tension and tension within their families and discrimination.

This is no doubt why the missionaries, Eichenbergers and Wildermuth-Holzers, were not allowed to visit a grammar school in their home due to what was perceived to be their low intellectual capabilities. After having had three children, Charlotte von Graffenried had problems in her marriage. As the documentary African Mirror by Mischa Hedinger revealed in 2019, Gardi was found guilty of being a pedophile in 1945 and was sentenced by the Bernese high court to a conditional prison sentence and a ten-year ban from practicing his profession.

Could it be that these travelers, missionaries and researchers were all looking for alternatives for personal reasons and tried to find their salvation in the distant Africa?

“It was the urge to explore, but also dissatisfaction with their everyday lives, social tension and tension within their families as well as discrimination that caused Swiss citizens to travel to Africa.”

The response to Gardi’s reports on the Mafa was also positive in his home country, resulting in him being vindicated. In 1967, the University of Bern awarded Gardi an honorary doctorate in ethnology for his “Mandara”. The University of Bern considered withdrawing the honorary doctorate in 2020, but came to the conclusion that, legally, this was not possible: As a dead person is no longer the holder of a title, it is in fact impossible to revoke a title. In 2004, a street in Bern was named after René Gardi, although this was later renamed Wankdorfstrasse.

Upgraded Bernese, downgraded Mafa

In their detailed documentation of our lifeforms, the Swiss Africa travelers were not looking to produce a precise and impartial description. The widespread image is part of the colonial and racist narrative which shows the travelers as ‘wise’ men, as patrons and corroborates the alleged superiority of the Europeans. The Mafa, on the other hand, are portrayed as silent, primitive figures. Most of the characters are depicted negatively. They were very often compared to Swiss people from the Cantons of Uri, Valais and other Alpine cantons, with those Swiss citizens who I today could see as my ‘sisters and brothers’, particularly as Gardi presents them to us as wild, barbaric and primitive in his travelogues.

My ancestors, as hosts to the Swiss travelers, knew nothing of this disparaging picture. They gave them all a warm welcome, they also ceded land to them so they could set up their missions. After all, the tradition of the Mafa dictates that you receive a stranger in a friendly manner. They were only defensive when they saw their culture being threatened and women raped.

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.

It is not only the violation of trust back then in the encounters between the Mafa and the Swiss travelers that is problematic, but also the updating and reinforcing of the pictures presented at that time today. I am concerned that the documentary already mentioned – “African Mirror” – by my friend Mischa Hedinger simply reproduced Gardi’s film sequences and pictures without commenting on them and without referring to their time of origin, resulting in a positive response among the Swiss public. The fact that he presented an image of starving, naked and sick black people, was not only trivialized by critics, but the movie received multiple awards.

Encounters continue

But Africa is a cradle of humanity and human values. Specific contacts were the result of the encounters described here, people influenced each other. The Bernese changed their world view in Mafa country. This is shown not only by a naturalization application by family Eichenberger in Cameroon, their and also Gardi’s wish to die and be buried with the Mafa, but also their works – school buildings, chapels and medical centers in Mafa country – that can still be seen today.

The travelers also personally valued objects from the Mafa culture: I have seen baskets, stones, fabrics, jugs, pieces of iron and even medicinal herbs in Swiss families of former travelers even today.

Exhibitions in Basel and Solothurn

Elisabeth and Paul Stulz, who looked after projects in the Mafa mountains in the 1980s and have returned on a regular basis ever since, show that these encounters continue and are nurtured. The Mafa see them as the adoptive parents of Mbafai, who today is married to a Swiss man. They also opened the door to Switzerland for me and my research project. The great interest of visitors to the current exhibition “Alive” in the MKB, in particular at the stand showing the Mafa soul jars, shows that something substantial has remained from this contact.

For example, the exhibition inspired Basel-based artist Regula Hurten to hold a photo exhibition in September 2024 on the subject “Körper im Raum – Körper als Raum” (Body in Space – Body as Space) in Solothurn, an exhibition in which the Mafa vray was the central concept as the vray offers space to a dead person’s soul while at the same time giving it an earthly presence.

Tevodai Mambai

is working on his doctorate at the Institute of Germanic Languages and Literatures at the University of Bern on the subject of the “Representation of mountain dwellers in selected post-colonial German-speaking travelogues on North Cameroon and North East Nigeria» with Prof. Dr. Melanie Rohner.

Contact: tevodai.mambai@students.unibe.ch

Magazine uniFOKUS

Africa

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS focuses on one specialist area from different points of view. Current focus topic: Africa

Subscribe to uniFOKUS magazine