Dialect research

Changing Swiss dialects

Swiss dialects are changing constantly and differ from one region to the next. Adrian Leemann and his team at the Center for the Study of Language and Society of the University of Bern have performed the first-ever large-scale analysis of the evolution of the Swiss language.

The video is only available in German.

Adrian Leemann: It’s common knowledge that language is in a constant state of flux and that young people, for example, are more likely to use new forms. I’m interested in new approaches and want like to find out which unknown factors play a role in language change. Since we’re conducting a first-ever study on the extent to which a speaker’s personality characteristics play a role in language change, we collected data about speakers’ personalities. What we found out is that extroverted people with a low level of conscientiousness were most likely to adopt and spread new forms; they might be more likely to say something akin to “themies” instead of “themes”.

Why is that important from a scientific point of view?Our research is important because it closes a gap. The last nationwide effort to document different linguistic levels took place 70 to 80 years ago. The results were published in the eight-volume series entitled “Linguistic Atlas of German-Speaking Switzerland” (Sprachatlas der Deutschen Schweiz). This atlas provides information, including phonetics, about the dialects and points out regional differences.

Nowadays we know that the dialects have changed from time to time, but there have hardly ever been any large-scale studies aimed at systematically exploring the changes in the Swiss German dialects. That’s a gap that we’d now like to fill. We surveyed more than 1,000 people in German-speaking Switzerland over the past five years and mapped the data with the goal of identifying the regions where the language underwent the greatest changes and why. Our research should help refine theories of linguistic change.

One interesting example is the word “schlööfle”, which means “ice skating” in the Bernese dialect. While this word only popped up occasionally in data compiled in the 1940s and 1950s in the city of Bern, our current data revealed that “schlööfle” is now said by a large share of the Canton of Bern and that most of the other expressions, including “schlittschuene”, have fallen out of use within the canton.

A lot of people are interested in how the cantons and regions differ from one another, including linguistically. Since our dialect is a huge part of our identity, people are extremely interested in the various dialects found in Switzerland.

The diversity found in Swiss dialects can also produce some really funny situations. In the city of Fribourg, the crust that’s left over in the fondue pot is called “Religieuse”. Now picture somebody asking you whether you’d like to eat “Religieuse”, which sounds a lot like it could mean “religious people”. Things like that could get people talking.

About the person

Adrian Leemann

Adrian Leemann earned his doctorate in Bern. He then spent some time as a postdoc at the universities of Zurich and Cambridge before becoming an assistant professor for Language Variation and Change at the University of Lancaster (UK) in 2017. He joined the University of Bern in September 2019, where he worked as a professor (SNSF Eccellenza) at the Center for the Study of Language and Society (CSLS). Since 2022 he has been a full professor at the Institute of Germanic Languages and Literatures of the University of Bern, where he explores language and society, (forensic) phonetics, dialects and innovative linguistic methods.

I’m fascinated not only by regional differences in the language but also by people’s different vocal qualities. I’m also very interested in forensic applications. Dialectological research can be highly useful for threatening phone calls, for example. Language can give us clues about a caller’s origin, age, gender and other social factors.

So we’re refining theories and extracting theoretical insights about the applicability of linguistic research. That’s one aspect of this field of research that I like best: its close proximity to people.

For our research, we had planned to compare historical data against current data. Over 500 towns were surveyed to generate the historical data presented in the Linguistic Atlas of German-Speaking Switzerland. Nowadays, that wouldn’t be feasible within a five-year period. We ultimately narrowed our scope down to 127 towns and had to make sure that our selection reflected the diversity of the dialects and that it could be meaningfully studied.

How is the research project being funded?The project is being funded by the Swiss National Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). We were also supported by the Research Foundation of the University of Bern, which enabled us to purchase the equipment.

This interview also appears in the Anzeiger Region Bern.

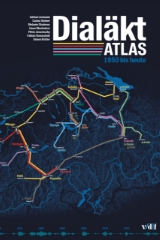

Dialect Atlas

Adrian Leemann – together with Carina Steiner, Melanie Studerus, Linus Oberholzer, Péter Jeszenszky, Fabian Tomaschek and Simon Kistler – will publish their Dialect Atlas, the product of a five-year research project, in November. This Dialect Atlas is a mapped collection of nearly 200 Swiss-German linguistic phenomena and regional variations that reveals how the Swiss-German language has changed from 1950 to today. The Atlas offers fascinating insights into the diversity of Swiss dialects and their evolution.

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.