Environmental history

Lessons from the “Wooden Age” of Pre-Modernism

The limited resources available to generate energy and seasonal fluctuations were defining issues even before the Industrial Revolution and required forward thinking. The term sustainability also appears in this context for the first time.

The limited resources available to generate energy and seasonal fluctuations were defining issues even before the Industrial Revolution and required forward thinking. The term sustainability also appears in this context for the first time.

Nobles restrict free use of forests

It was not until the 14th to 16th centuries that the use of forests was subject to increasingly restrictive regulations. Cities had police regulations stipulating who was allowed to remove how much wood at what times. Aristocratic and ecclesiastical forest owners also tried to ban the free use of forests and the harvesting of timber by the peasant population.

In addition to wood, water and wind were mainly used as energy sources. Rivers also served as transport routes, for example to transport wood from the forested mountainous regions to the more densely populated pre-Alpine areas.

But water also drove different types of mills. The grain mills were just one of many uses. Water-powered ore mills were also used in smelting, in which the rock transported from the mine was reduced to granules before it was sent to the smelting furnaces. Until the 19th century, linen rags were initially reduced by machine as a raw material for paper production in paper mills.

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.

Not only wood, but water and wind as energy sources

In northern central Europe, the use of wind energy also played a key role at an early stage. The lowlands on the North Sea were only able to use the large rivers for hydropower, whereas smaller watercourses had insufficient gradients. But the windmills that still dominate the landscape in places today didn’t just grind grain: Most of the mills were used to drain the fields, especially in the Netherlands, where the inland areas below sea level were gradually converted into arable land.

Mining caused forests to disappear

By far the largest consumers of energy were mining operations, salt works and glass blowers. In mining, the wood was used not only for tunnel construction, but also for smelting furnaces. As a result, the forests of the mining regions were quickly cut down, which meant that the wood had to be brought from ever more distant areas. This manifests itself in the sources, for example, through frequent reports of avalanches.

Salt mining, with its centers in the Eastern Alps, but also in southern Poland, has been based on wet mining since the High Middle Ages, i.e. water was channeled into the salt-bearing layers of the mountains, gradually forming an underground lake. Once the natural brine was finally saturated, it was channeled to salt pans in the valley, where the salt was boiled in large boiling pans, pressed into large cone stumps and transported on the river. The firewood was supplied by a nationwide rafting system.

The glass industry was also very resource-intensive, so it settled in wood-rich regions such as the Bavarian Forest. Soon, companies began planting fast-growing spruce or pine forests, which laid the foundation for highly vulnerable monocultures some 300 years ago.

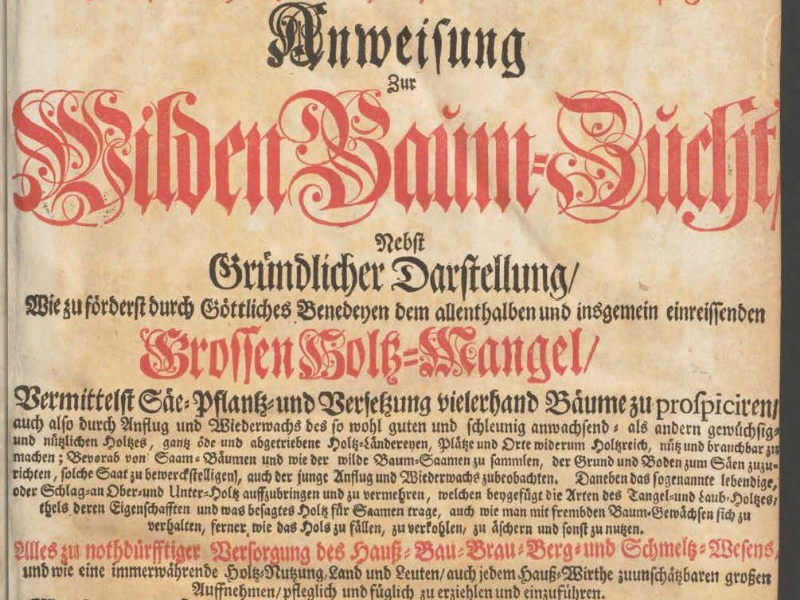

The invention of sustainability

The high demand for wood for mining and the increasing shortage of wood in the immediate vicinity were also addressed in the treatises of forest economists in the early 18th century. Hans Carl von Carlowitz dedicated his work “Sylvicultura oeconomica” (Economic Forestry) to this question in 1713. In it, he advocates the “sustainable use” of forests – the first explicit evidence of what has now become an essential guiding principle today. However, he primarily understood this to mean the long-term economic benefits; there is no mention of the other two sides of sustainability, i.e. a balance also in ecological and social terms.

“Fixing to a specific energy source can quickly lead to bottlenecks.”

Christian Rohr

The different water levels of the rivers according to the season always presented a challenge. If the water level was too high or too low, some of the waterways could no longer be used to transport people, commercial goods and, above all, wood. The mills on the riverbank were also affected, so a different type of mill developed as a way out: In boat mills, the mill wheels were mounted on or between several ships and could be adapted to the current conditions to suit the water level. The different wind conditions also led to seasonal fluctuations in the use of windmills and in sailing ship traffic.

About the person

Prof. Dr. Christian Rohr

has been Full Professor of Environmental and Climate History at the Historical Institute of the University of Bern since 2010. He focuses on issues of resource use, how to deal with extreme natural events, the relationship between the environment and tourism, and the analysis of historical picture sources.

Prof. Dr. Christian Rohr

Insights for today’s challenges

Looking back reveals challenges that continue to shape the energy sector today, such as the seasonal availability of renewable energies. Whereas in the Pre-Modern era economic life had to adapt to the respective availability of energy sources, today we need an optimized mix of energy sources and, above all, storage options for surplus production. And the historical dependence on wood also shows that fixation on a specific energy source can quickly lead to shortages if availability is at risk – for whatever reason.

Magazine uniFOKUS

People need energy

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS focuses on one specialist area from different points of view. Current focus topic: Energy

Subscribe to uniFOKUS magazine