Study on "ecological debt"

Heat extremes cause long-term damage to ecosystems

Ecosystems use different strategies to protect themselves from the negative effects of heat extremes. A study by the University of Bern shows: The full extent of the ecological impact only becomes apparent after the end of a heat extreme.

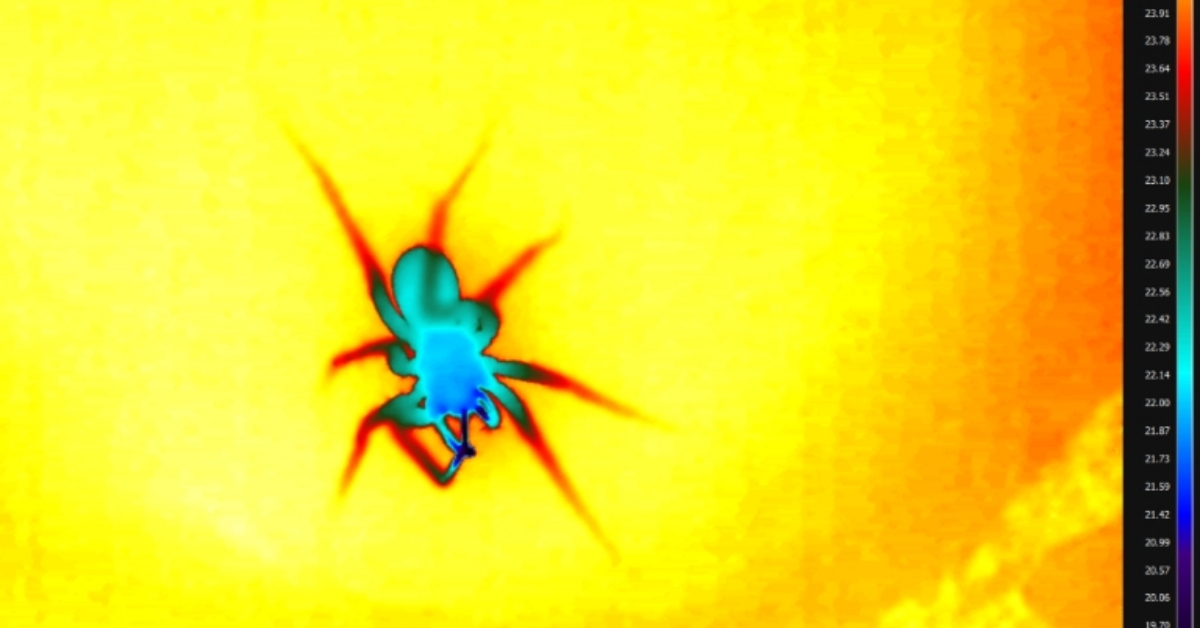

Climate change is causing heat extremes to occur more frequently and become more severe. This presents nature with challenges to which it responds with different strategies. For example, most animals seek for cooler refugia and reduce their activities to avoid overheating. Many of these strategies have been well studied scientifically. However, it has remained largely unexplored, whether and what ‘ecological debts’ arise for organisms after such heat extremes.

The ecological debts of heat extremes

This is where the review by Gerard Martínez-De León and Madhav P. Thakur from the Institute of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Bern becomes relevant. The two researchers have conducted an extensive review of over 100 studies that investigated the responses of ecosystems to heat extremes and concluded that they are associated with so-called ‘ecological debts’ that only become apparent after the end of a heat extreme. “Ecological debts are, for example, reductions in the population size of an organism because they reproduce less strongly due to a heat extreme or shifts in species composition as native plants are displaced by invasive non-native plants that recover and establish faster after a heat extreme. In principle, we can often only detect such costs after the organisms have been able to recover at optimal temperatures,” explains co-author Thakur. “By neglecting the temporal component, we are underestimating the impacts of heat extremes in many contemporary studies,” says co-author Thakur, head of the Terrestrial Ecology research group at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution.

Creating opportunities for ecosystem recovery

“As climate change progresses, it is crucial to understand the long-term impacts of heat extremes on natural and agricultural ecosystems. Impacts on agricultural ecosystems can be seen, for example, when invasive pest species use heat extremes as windows of opportunity to recover and establish faster than the native species,” stresses co-author Martínez-De León. As the ecological consequences of heat extremes can accumulate over time, it is necessary to enhance the resilience of ecosystems to climate change, says the researcher. To achieve this, species must be provided with the required conditions for their recovery. “This includes, for example, improving the availability of cooler and well-connected habitats, where species can disperse, allowing native species to persist and recolonize quickly after heat extremes,” explains Martínez-De León.

Publication details

Gerard Martínez-De León, Madhav P. Thakur: Ecological debts induced by heat extremes, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 29. Juli 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2024.07.002

About the person

Gerard Martínez-De León

is a PhD student at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Bern and part of the Terrestrial Ecology research group.

About the person

Madhav P. Thakur

is professor of ecology, and head of the Terrestrial Ecology Division at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Bern. His division’s research focuses on the impact of climate change on biodiversity.