Thomas Stocker is given emeritus status

“Climate research in Bern is a brand”

Thomas Stocker is one of the figureheads of the University of Bern and a climate researcher of international renown. Among other things, he had a leading position on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Now, he is being given emeritus status. In this interview, he takes a look back at his career, tells us about an offer he once received from Cambridge and talks about orchids and racing bikes.

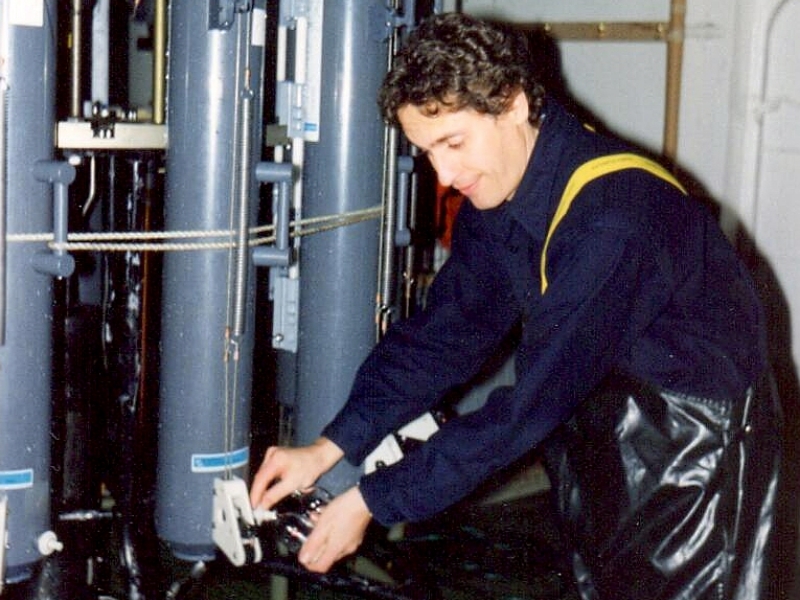

Thomas Stocker:Thomas Stocker: I started off with physics although there were lots of other things I was interested in. In 1980, I was given the opportunity, as a student, to complete a two-month spell working at the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research on the Weissfluhjoch where I carried out simulations on the stability of the snow pack. That was when I realized just how fascinated I was by the Earth system. By chance, I heard about a new degree program at ETH Zurich called environmental physics that I then opted for and completed. My degree and my doctorate were extremely interesting but also quite theoretical: I focused on wave propagation in rotating channels and lakes. After a short postdoc on the same subject in London, the topic appeared to me a bit too limited; I wanted to open up my horizons. An opportunity came along to go to McGill University in Montreal, where a climate research group was being set up at the time.

Climate research fascinated me from the very beginning but, just like today, you would shimmy your way from one postdoc to the next and not know whether you had a long-term perspective in research. That is why, while I was doing my doctorate at ETH, I also obtained a high school teaching certificate in physics, so I did have a plan B although I never actually had to use it.

“Just like today, you would shimmy your way from one postdoc to the next and not know whether you had a long-term perspective in research.”

Thomas Stocker

Then at the first ProClim Conference in Locarno in 1990, I met an eminent researcher from the US, Wally Broecker. We got talking and he asked me whether I could imagine joining him at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University near New York. At the time, that place was world number one in paleoclimate research, specifically the reconstruction of the climate of former times – a fantastic offer. And, at that time, Broecker put forward an interesting hypothesis that ocean currents can change very quickly and that this may be the reason for the abrupt changes in temperature in climate history that had been found in the Greenland ice cores. Broecker called them Dansgaard-Oeschger events, a term that is now commonly used.

I was so excited and thought I had my next post. And then Wally Broecker got in touch with me a few months later and explained I would first have to submit a research proposal to the Department of Energy in the US. In the end, the project was approved, and my salary secured. I originally wanted to stay in New York for four years, but after two years, I got a phone call from Bern …

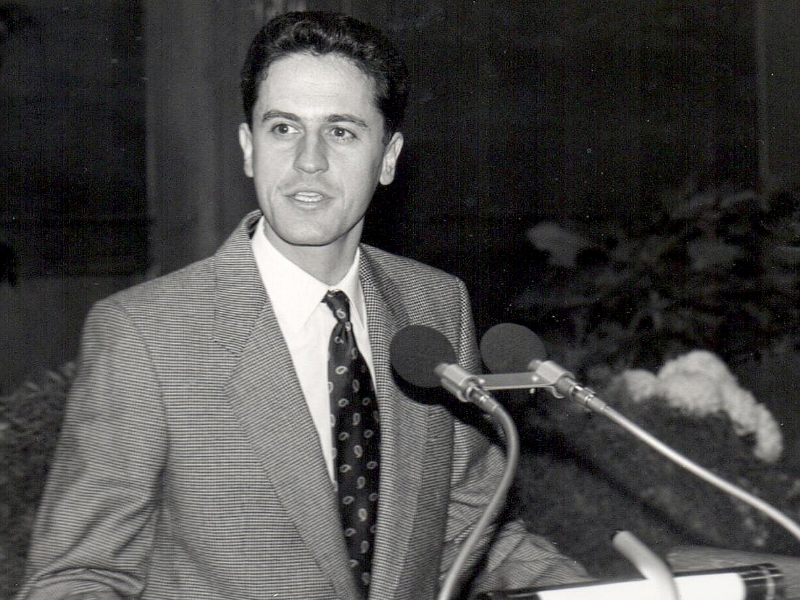

And they suggested you apply for a professorship?That’s right. A year earlier, Hans Oeschger had already sent me the job ad looking for his successor and made me aware of the position. But I hadn’t replied because I was just a young postdoc and would never in a million years have thought of applying for a position which at the time, 1992, was the only professorship in Switzerland that dealt with climate change of the past few 100,000 years and the future.

So they pushed you a little?The selection committee from the University of Bern was back to square one after the first round as their preferred candidate had turned them down. They then asked around in the community to see if anyone could put forward an interesting candidate, and I was lucky that my boss in Lamont, Wally Broecker, felt there was no reason why I couldn’t continue my research in Bern and recommended me …

… and so then you were actually selected at the age of just 34 …… yes, and when I got to Bern, my knees were shaking, and I wondered whether the whole thing would actually work out. In one fell swoop, I was responsible for a whole department at the Physics Institute which totaled 28 people, some of whom had long-term experience, who had been involved in international research. And then some youngster comes along from America and takes over the department. But it worked – mind you, only thanks to the fantastic colleagues I had the privilege of joining and working with.

“When I got to Bern, my knees were shaking, and I wondered whether the whole thing would actually work out.”

Thomas Stocker

When you started to get interested in climate research, nobody knew just how significant this issue would become. Does your career also have something to do with the fact that you were waiting in the wings at just the right time?It is true that climate research really took off at the end of the 1980s. And the Department for Climate and Environmental Physics set up by Hans Oeschger at the University of Bern was on the front line – on the one hand, with the understanding of the climate system thanks to the analyses of ice cores on the basis of which Hans Oeschger and his team were able to prove that the increase in greenhouse gases since industrialization was man-made and the concentrations during the Ice Age were considerably lower. And, on the other, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was founded in 1988 with the purpose of compiling a first scientific assessment report on previous and possible future climate change and illustrating possible courses of action to be presented at the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992. The University of Bern already played a leading role in this first report.

And that is when politics and the general public really started to be interested. In a way, you became the face of climate research in Switzerland …… that sort of just happened. The requests came along, and I was available. It wasn’t like it is today, where you have to have a strong presence in social media to get noticed.

Did you enjoy your role explaining climate change in the media?Yes, definitely. I certainly never did a home story in one of the popular Swiss magazines, such as “Schweizer Illustrierte”, but it gave me a great sense of satisfaction not just to come craft robust statements that were accepted by consensus, but also to communicate these to the public. It is the job of science to create knowledge, as well as to share it, particularly when it comes to a topic which has such great social relevance.

As long as I was Co-Chair of the IPCC I never leaned out of the window because I didn’t want to influence the assessment process.

“If a political party tries to manipulate public opinion with propaganda, I will certainly point that out.”

Thomas Stocker

But recently you have done. You certainly didn’t veil your criticism of the Swiss People’s Party (SVP). You didn’t exactly mince your words.That’s true. I think with my experience that is something you have to do. I don’t mince my words when it comes to blatant attempts at influencing before a vote. If a political party tries to manipulate public opinion with propaganda, I will certainly point that out.

Now you are being given emeritus status and are thus no longer a representative of the University of Bern for the general public. Are you even less likely to mince your words now?No. What is important is that what I say is still based on scientific facts. That has always been my ambition: To address things in a pointed and comprehensible way while, at the same time, always providing in-depth information.

So you are not going to become a second Jacques Dubochet, the winner of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry from the University of Lausanne, who sympathizes with the climate activists?I really admire what Jacques does. I’m certainly not as much in the limelight as him but a few years ago, for example, I was really committed to the climate youth group in the Canton of Glarus, which actually led to a candidate of the Green Party being voted onto the Council of States and also to genuine climate protection being written into law. This was decided upon in the cantonal assembly, namely a ban on oil heating systems.

What would you say was the greatest success of your academic career?For me, the most important thing is that today the Department for Climate and Environmental Physics is in a very solid position and is a powerful international brand on the map. But I can’t take credit for that, it is the result of the joint achievement of all our staff, students, postdocs, scientists and professors who have enabled and carried out research, and have been committed to teaching over the past 30 years.

“For me, the most important thing is that today the Department for Climate and Environmental Physics is in a very solid position and is a powerful international brand on the map.”

Thomas Stocker

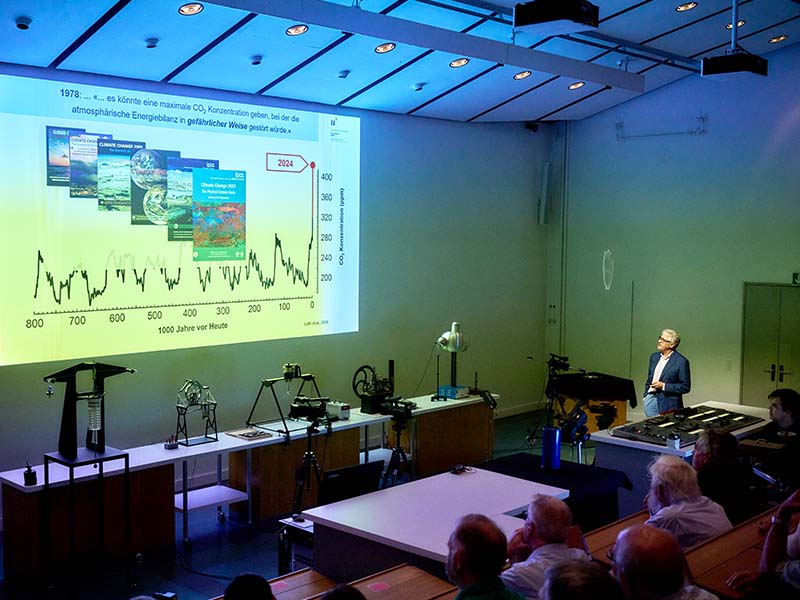

Allow me to ask you something else about your personal highlights: Which of your more than 260 papers has been cited most often?That would be the publications about the reconstruction of CO2 and CH4 concentrations over the last 800,000 years with the help of ice cores that we were able to complete as part of the European project EPICA. That’s still a world record today. Our second successful area is the modeling of the climate system with what are referred to as models of reduced complexity. With these simplified climate models, which are essential for understanding our measurements on polar ice cores, we can run extremely efficient simulations and test hypotheses. Despite the simplicity of these models, we are still able to keep up at an international level.

When people retire, they often get asked about their hobbies: In your case, I have heard that you like riding your racing bike and that you cultivate orchids. Is that true?I’ve never cultivated orchids. But yes, I have always been interested in native orchids. It’s a virus I caught from my biology teacher at high school. I spent years collecting literature about these flowers and always looked out for them whenever I was on hikes. There are over 40 native types of orchids in Switzerland – all of them endangered species. I also went through a phase of collecting old botanical illustrations from the 18th century – I was totally fascinated back then, but today that passion has somewhat faded. Somehow, it’s relatively easy for me to get interested in new things and then I like getting to the bottom of them.

And going out on your racing bike?I started doing that during the pandemic. Luckily, I listened to the urgent advice of my daughters and bought a racing bike before things started to get difficult with delivery. Since then, I’ve been riding around Bern and its environments. Last Saturday, for example, I was out biking with my daughter in the area of Schwarzenburg. We covered a distance of 70 kilometers and a difference in altitude of 1,300 meters. That was fantastic.

“Looking back, I have to say that this defeat was in fact the best thing that could have happened to me.”

Thomas Stocker

Alongside all your successes, you have had a few failures. You would have liked to have been selected as Chair of the IPCC in 2015, but weren’t. Was that a very painful experience?Yes, it did get me down, but not for long. And, looking back, I have to say that this defeat was in fact the best thing that could have happened to me. I discovered that global competition at this global level becomes very political, whereas my office as Co-Chair of the IPCC working group “Physical Science Basis”, was, as the name suggests, very scientific. And with politics, you are subject to very different forces.

Yes, I did know, but what I didn’t realize is that in this sphere, science has no place. That was certainly somewhat naive.

For decades, you were a figurehead in science. Were there never any “poaching” attempts? Did you ever have a headhunter come to your office and make you an irresistible offer?I had a few offers, yes. One of them was to become a professor at the University of Cambridge. Naturally, when you get an offer from a university of that caliber you instantly find it fantastic and know it is something you should look into. Their plan was to set up an interdisciplinary climate research center like the one we have at the University of Bern with the Oeschger Center. When I asked about the budget available to set it up, the Dean replied: ten thousand pounds a year. I had to laugh and told him that in my department I would use that kind of money to organize a seminar for two semesters. And that was the end of the conversation.

No, but I hope that I conveyed to both Anna and Francesca a passion for nature and natural sciences. The elder of the two studied physics at the University of Bern and the younger one was also here but did biochemistry. Now, one works with the Swiss Federal Administration and the other works in the pharmaceutical industry. Both are happy with the paths they have chosen.

The same thing again, no doubt about it: environmental physics.

About the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research

The Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research (OCCR) is a leading institution for climate research, it carries out interdisciplinary research that is at the forefront of climate science. The OCCR brings together researchers from 17 institutes and 5 faculties. It was founded in 2007 and is named after Hans Oeschger (1927-1998), a pioneer of modern climate research and predecessor of Thomas Stocker.

Learn more

https://www.oeschger.unibe.ch/index_eng.html

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.