Biodiversity

Revitalizing the river here will pay off

Fish are one of the most endangered animals in Switzerland, mainly due to the obstructed waters. A project by the Wyss Academy for Nature, the University of Bern and the Eawag Aquatic Research Institute is helping with renaturation.

The frozen forest floor crunches beneath our feet as we march along the banks of the Sense in the Fribourg municipality of Plaffeien. Here the river is 200 to 300 meters wide and the main stream divides into three branches. Tree trunks are piling up, piles of brush have become entangled in small dams, in front of which the debris collects. “This is one of the last great wild rivers, the vast majority of which have been seriously negatively impacted by humans,” explains Conor Waldock of the Institute of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Bern. The water rushes almost unhindered over a distance of 30 kilometers towards the Swiss Plateau, a rarity in our country of fragmented rivers and streams. Due to flooding and dead wood and debris carried along by the water, the river regularly sculpts a new stream bed and spreads out over the banks.

Diverse habitat

What seems chaotic above ground offers the ideal living conditions below the water level for fish species such as brown trout, bullhead or minnow: On one hand, many fish species depend on river sections with strong currents and gravelly beds for their reproduction, while, on the other hand, the side branches with shallow and calm water are ideal nurseries for the young, which do not have enough strength to swim against the main current. In addition, washed-up dead wood provides protection and structure for habitats and serves as a substrate for algae and insect larvae, which are in turn an important food source for fish.

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.

The site is also valuable for the life cycle of many other animals and plants due to its wetland character. For example, the now rare German tamarisk colonizes the riverbank. Waldock is out and about with his institute colleague Bernhard Wegscheider today. Both scientists are currently mainly involved in the “Stopping the loss of freshwater biodiversity – despite climate change” project.

“Stop and go” in streams and rivers

The six-year project, which is funded by the Wyss Academy for Nature, the Canton of Bern and the Federal Office for the Environment, aims to provide Swiss fish with more habitats. This is urgently needed, as the project team has proved that 90 percent of potential habitats are being negatively impacted by human activities; in every second case, the fish find it difficult to survive due to multiple human interventions. There are 100,000 obstructing features in this country; on average, the longitudinal flow of the rivers is interrupted every 600 meters.

Climate change exacerbating the problem

Concrete barriers were built decades ago to generate electricity from hydropower, irrigate agricultural land, and protect infrastructure and settlements from flooding. “But barriers and straightening make the water space barren and unattractive for many fish species,” says Waldock. The structures also prevent the animals from moving through the river network. This is particularly critical because climate change is also making the waters warmer and specific species want to retreat to higher areas.

"90 per cent of potential fish habitats are negatively impacted by human activities; in half of river sections there are multiple human interventions acting negatively together."

Conor Waldock

Renaturation reaches its limits

We stop briefly at the Limpach in the Bernese community of Fraubrunnen, a meager, predominantly canalized and straightened little stream. But as it turns out, even such banal channels sometimes have a lot of biological diversity to offer: “Surprisingly, our investigations have identified eight fish species here, even if they are not the most endangered,” explains Waldock. 80 years ago, when the Limpach was occasionally lost to the swampland, the water was probably even more diverse. It probably also provided shelter for species such as the Misgurnus, which are now much rarer or extinct in Switzerland.

The wetland has since been drained and peat cutting is a thing of the past. “Rewetting would be biologically desirable, but probably does not stand a chance politically because too much land would be affected,” concedes the biologist. It would at least make sense to remove embankments from the brooksides and to revitalize them with plants: “The fish need shady and cooler stretches of water to survive the summers, which are getting ever warmer with climate change.”

A dam separates habitats

Renaturation is already being implemented on a section of the Sense on the Oberflamatt elevation: The embankments have been removed here and the river now meanders on wide gravel banks instead. The River Emme is also being upgraded: a generous streambed has been restored in the Ämmeschache-Urtenesumpf nature reserve, making it look almost as wild here as the Sense upstream. “Even though the restoration has been successful, there is still a lot to be done, because the effect only extends as far as the dam,” explains Waldock: The nature reserve is home to seven species of fish, but only two above the dam. From an ecological point of view, the next important step would be to restore the Emme’s longitudinal network, as the migration obstacles along the entire river pose a major problem for biodiversity.

"Barriers and straightening make the water space barren and unattractive for many fish species."

Conor Waldock

Concreted and culverted

Like the other cantons, the canton of Bern is working on the long-term renaturation of stretches of water. But which river and which section has priority? Does it make sense to renature a river arm if a cascade of dams downstream prevents fish from migrating between different habitats and causes the population to dwindle? Does revitalization make sense if the “missing species” that will colonize the new habitat would not actually live here naturally?

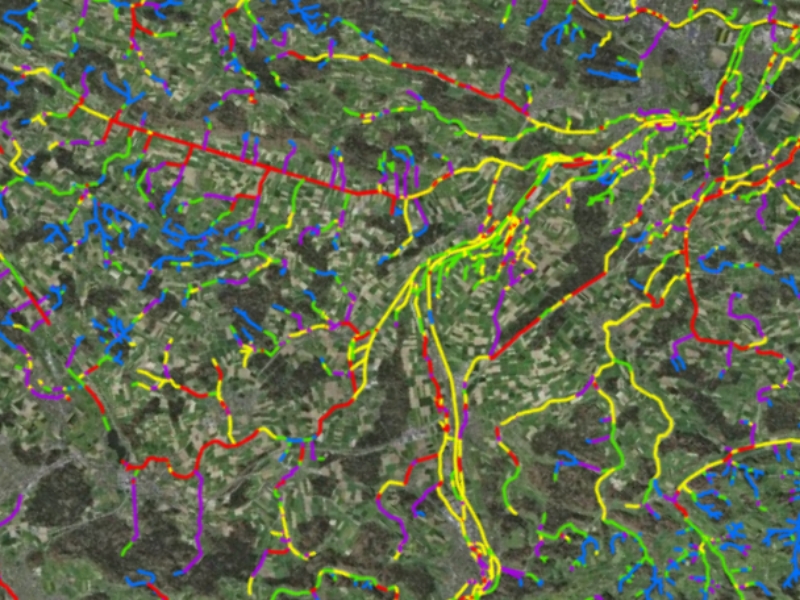

The researchers later show us what we saw in nature on a screen at the Institute: As part of the project, the team developed a study to show which section could theoretically harbor which fish species at 15,000 measurement points in the Rhine and Aare catchment areas. All watercourses are marked with different colors on a digital map. The Sense, for example, is almost continuously blue in color until it flows into the Saane near Laupen. Blue means: The river is practically a biodiverse paragon. But blue is rarely on the map. Most bodies of water are so impacted by humans that the blue changes to green, yellow, purple – or even red. The warning color indicates that the water is scarcely habitable for even the most undemanding fish species.

AI assesses “shadow distribution”

The mapping is based on cantonal surveys, which the research team supplemented at certain points with its own fish censuses – Bernhard Wegscheider recalls it being a laborious affair, “We did the first census using electrofishing in cold January – we then scheduled the majority of the measurement series for the summer and fall.” The data collection was necessary to feed “explainable artificial intelligence” models, an innovation in Swiss environmental management. It is intended to help decipher and explain the impacts on the individual species in the rivers.

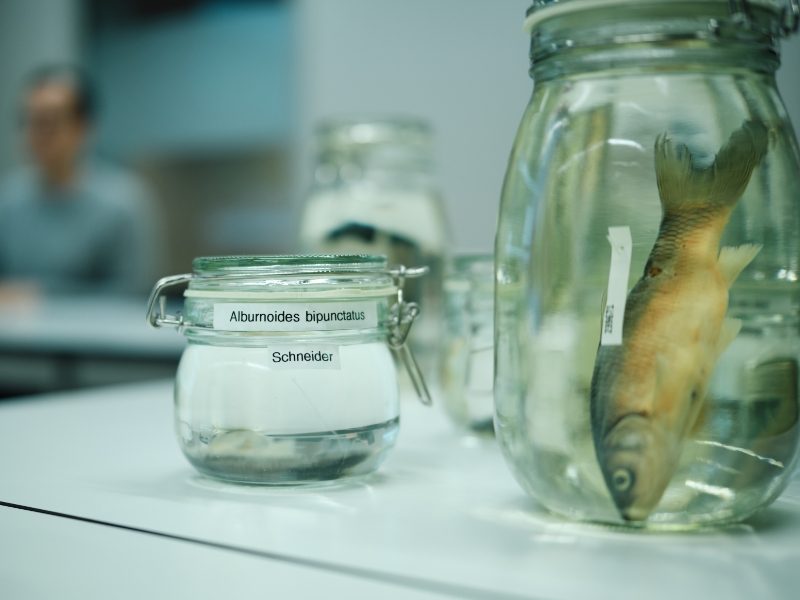

This allowed the team to find out how and where humans had the greatest impact. With the support of AI, it was shown that, for example, the endangered schneider fish could actually live in 40 percent of the waters in this country – but has only survived in 4 percent. The study introduces the term “shadow distribution” for the potential if human interventions were remedied. Waldock says, “We hope that these findings will help guide restoration efforts and improve fish biodiversity in Switzerland.”

Valuable caddis fly

Waldock sees the fish as an ideal object to show how species develop under human impact. “Terrestrial animals are more complicated as they are more flexible than aquatic life. This is because they can switch to another location more easily when the habitat no longer suits them.” Nevertheless, the AI-based concept will soon be used to show how human interventions negatively impact the fauna for other animal species – and how these can be reversed as efficiently as possible.

Surveys for insects that live in water in their larval stage and later in the vicinity of the watercourse are already in progress. Bernhard Wegscheider says, “Our studies show that the number of these small animals is decreasing due to pesticides from neighboring agriculture.” This also affects birds that eat aquatic insects such as the mayfly, stone fly and caddis fly. If these representatives of so-called macroinvertebrates are missing, the birds will find alternative food. But this alternative diet is less nutritious because the larvae of mayflies and other flies feed on algae that contain particularly high-quality unsaturated fatty acids. The foraging process therefore becomes more laborious for birds.

Wegscheider says the example shows that the isolated renaturation of a stretch of river is not enough and that the ecosystem and society must also be taken into account, “That is why three social scientists are also represented in the project team.” Their task is to understand why enforcement is stagnating and how biodiversity in the waters can be improved together with local stakeholders. The aim is to ensure that society supports the transformation into a near-natural habitat and thus secures it in the long term.

Putting knowledge into practice

The six-year project was deliberately designed in such a way that the scientific findings can be put into practice. This will provide enforcement authorities at all levels of government with tools to improve the enforcement of existing laws. The second pillar of the project therefore involves participatory work with the relevant authorities. Co-project manager Adrian Aeschlimann from the Schweizerisches Kompetenzzentrum Fischerei (SKF) contributes the practical knowledge required for this. “It is important to get the relevant stakeholders on board at an early stage,” says Aeschlimann. He points out possible hurdles, such as the fact that many authorities are already involved in cantonal administration alone when it comes to water renaturation: “They range from the energy industry to agriculture and fisheries control – and often lack knowledge about the needs of biodiversity.” In addition, there are the local communities responsible for waterways engineering and, depending on the situation, other groups such as local residents and nature conservation associations. The SKF wants to optimize the plans for a renaturation project in such a way that the newly acquired knowledge is implemented quickly. “The most expensive measure is not always the best,” says Aeschlimann. Sometimes it is low-cost stepping stones – or better stepping waters – that lead to networking and thus to a massive improvement in the quality of a stream.