From Anna Tumarkin to Virginia Richter

The history of women at the University of Bern

Julia Richers and Carmen Scheide critically trace the history of women at the University of Bern. Their expertise in the history of Eastern Europe is illuminating, as there was once a “Russian colony” in Bern.

Rector Hans von Scheel gave a remarkable keynote speech on the foundation day of the University of Bern in 1873. Under the title “The Question of Women and Women’s Studies”, he advocated the immediate opening of the University to women – after a balanced discussion of the reasons for and against admitting women to study.

The reason for his remarks was the attendance of 21 female students at the University of Bern, most of whom studied at the Faculty of Medicine. Hans von Scheel did not see the new women’s education movement as a “fashion fad of emancipated ladies that would quickly disappear”, but rather as a sociocultural change.

Women were increasingly “stepping out” of traditional family roles in order to earn their own livelihood. This should be supported and would not automatically lead to a dissolution of the social order. Access to the University for women ought to be regulated and placed on an equal footing with that of men in terms of admission requirements, and also in terms of origin.

A courageous step: Admission of women

“But since all of our universities have a cosmopolitan character, for their own good, in that they admit male foreigners, how can they close themselves off to female foreign students?” the Rector asked the audience present.

A year later, in 1874, the Department of Education of the Canton of Bern took up the arguments and issued regulations governing the admission of women to study at the University, where they could henceforth study without restrictions.

“The female pioneers from Eastern Europe were irritating and caused a stir in Bern, but they were trailblazers and paved the way for female Swiss academics.”

- Julia Richers and Carmen Scheide

The following is a historical overview of selected aspects of the new beginning and the challenges faced by women at the University of Bern. These include cosmopolitan internationalization and the role of female pioneers from Eastern Europe, as well as the rocky path for women in academia.

Female pioneers from Eastern Europe shape women’s studies

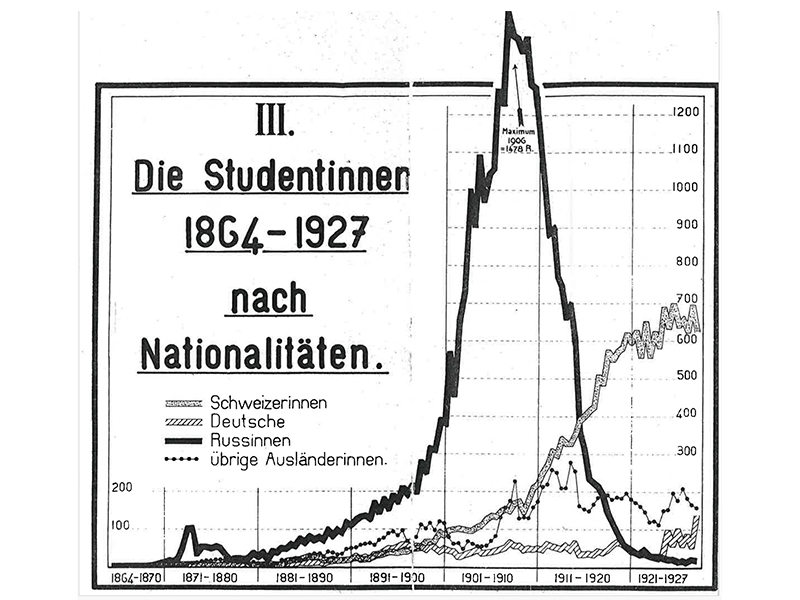

The history of women’s studies in Bern cannot be told without mentioning the first female pioneers from Eastern Europe. For more than 40 years, from 1874 to 1914, the majority of female students in Bern came from the Tsarist Empire, sometimes accounting for almost 90% of female students.

The reasons for this are manifold and can be traced back to the ambivalent policies of the Tsarist Empire on women’s education. After the first progressive opening of girls’ grammar schools and university lectures in the mid-1850s, the tsarist government restricted access again in the 1860s. In 1873, it even tried to prevent those women who had fled to liberal Switzerland to study from returning to Russia for their professional future by issuing a tsarist decree. The decree was directed against the University of Zurich as the “center of revolutionary propaganda”, where the students were “young girls under the influence of the revolutionary leaders” and, serving “moral decay”, would become “the willless tools of the same”.

“The newspapers spoke frankly about the ‘plague of Russians’ at the University of Bern.”

- Julia Richers and Carmen Scheide

Women made the University of Bern the largest university in Switzerland

After the fatal assassination of Tsar Alexander II. in 1881, the government further restricted access to education and, from 1887 to 1917, also introduced a numerus clausus with serious consequences for Jewish students. The only thing left for women and Jews was to go abroad. The young, cosmopolitan University of Bern came into the spotlight here and, by 1900, developed into the largest university in Switzerland.

Anna Tumarkin: First female professor with full rights

Perhaps the most prominent example of a female academic from the Tsarist Empire was Anna Tumarkin. In 1892, she came from the Bessarabian town of Kishinew/Chişinău (now Moldova) to Bern, where she passed her doctorate in philosophy with distinction in 1895. After studying in Berlin, she habilitated in Bern in 1898, became a lecturer, honorary professor and was finally promoted to associate professor in 1909. This made her the first female professor in Europe to be granted full examination and admission rights.

The “Russian colony” in Bern

In Bern, emigrants from the Tsarist Empire formed a living “Russian colony,” as it was called at that time. “The Russian colony lived in two quarters, Länggasse and Mattenhof,” wrote Vladimir Medem, the well- known socialist and representative of the General Jewish Workers’ Federation, in his memoirs. Anyone there “almost felt transported back into a Jewish shtetl”.

On closer inspection, however, this colony consisted of very different groupings: The revolutionary milieu, to which Lenin and Rosa Grimm belonged, gained fame and included not only Bolsheviks but also Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Also important was the Zionist and federalist milieu, which included Medem, Sophia Getzova and Chaim Weizmann. Finally, there was the group that had found its way to Bern out of purely academic interests, such as Tumarkin and the later school doctor and women’s rights activist Ida Hoff.

Resistance and prejudices

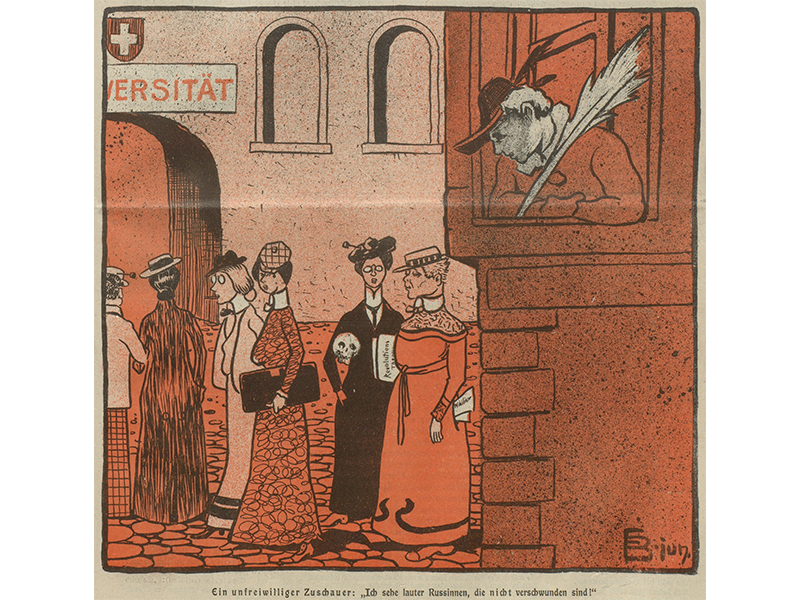

It was precisely the unusual sight of the large number of “Russian female students”, as the young academics from the Tsarist Empire were commonly referred to, that sparked a long-lasting debate in the Swiss press.

In 1904, a newspaper campaign broke out in the Bernese press entitled “Die russische Studentin” (The Russian Student), which sometimes had racist and anti-Semitic tendencies. And back in 1907/1908, the newspapers spoke frankly about the “plague of Russians” at the University of Bern. In the caustic contemporary caricatures of a popular satirical magazine of the time (“Nebelspalter”), the Russian women appeared as revolutionaries and bombers, as short-haired, bespectacled, androgynous creatures or as modern witches and poison mixers in white lab coats.

“The connection between the first female academics at the University of Bern and the subsequent women’s suffrage movement is striking.”

— Julia Richers and Carmen Scheide

Pioneers for female Swiss students

The female pioneers from Eastern Europe were irritating and caused a stir, but above all they were pioneers and trailblazers for female Swiss academics, the numbers of which only increased significantly with the outbreak of the First World War. In her treatise on women’s studies in Bern in 1928, Hedwig Anneler (1888–1969) summed up as follows: “Without these strangers, we might have found our way to university even later and even less often.”

For women’s suffrage

The connection between the first female academics at the University of Bern and the subsequent women’s suffrage movement is striking. A socio-political mobilization of young female students took place in the Female Student Association of the University of Bern, which was founded in 1899. Prominent examples of female academics who campaigned for political equality for women included biochemist Gertrud Woker, women’s rights activist Annie Leuch-Reineck and Tumarkin’s partner Ida Hoff. For these women, belonging to the women’s movement was “a matter of course, as they felt privileged through their studies and knew that [they] owed this privilege to the women’s movement,” remarked women’s rights activist Agnes Debrit-Vogel (1892–1974), looking back.

As is well known, women’s suffrage for Swiss women came later than hoped; it also took until 1964 before the University of Bern appointed the first full professor – legal scholar Irene Blumenstein-Steiner (1896–1984).

New women’s movement calls for equality

In the late 1980s, there was a new wave of demands for equality and the visibility of women in academia, including at the University of Bern. The association FemWiss was founded in 1988. In 1989, historian Beatrix Mesmer became the first woman and Vice-Rector to join the Executive Board of the University of Bern. The office for the advancement of women (AFF) was established in 1990. Important tasks included participating in appointment committees, representing the interests of women in academia through networking, career planning, setting up childcare places and further efforts to reconcile family and work.

With the changing discourse on women, their place in society and history, as well as power and gender relations, the office was renamed the Office for Gender Equality in 1998 (now the Office for Equal Opportunities). In 2011, Doris Wastl-Walter was appointed the first female Vice-Rector with responsibility for gender equality. She was followed by Silvia Schroer in 2017 and Heike Mayer in 2023.

The first female Rector after 150 years

Action plans, measures and guidelines on equality and diversity are in an ongoing development process, as are funding instruments for increasing the proportion of women at the University at all qualification levels.

Nevertheless, it took 150 years from the speech of Bern’s Rector Hans von Scheel and the introduction of women’s studies in 1874 before a woman, Virginia Richter, scholar of English, was appointed Head of the Executive Board of the University of Bern for the first time in 2024.

About the author

Julia Richers

is Professor of Modern General and Eastern European History at the University of Bern. She conducts research and works on the borders of Eastern Central Europe and the Soviet Union, as well as on the many interconnections between Switzerland and Eastern Europe.

Contact: Prof. Dr. Julia Richers: julia.richers@unibe.ch

About the author

Carmen Scheide

is a lecturer in the history of Eastern Europe at the University of Bern. She researches and works on cultures of remembrance, consequences of war and contemporary history in Eastern Europe, particularly in relation to the regions of Russia and Ukraine. She is also interested in both women’s history and gender history.

Contact: Dr. habil. Carmen Scheide carmen.scheide@unibe.ch

Exhibition: “Pioneers from Eastern Europe”

Julia Richers and Carmen Scheide and their students have put together an exhibition to mark the 150th anniversary of Anna Tumarkin's birth, which commemorates the pioneering years of women at the University of Bern:

The exhibition will be opened on Monday, February 17, 2025 at 2:30 pm by Rector Virginia Richter, the makers, Franziska Rogger and Nina Tumarkin on Tumarkinweg next to the main building (in case of bad weather in lecture hall 028).

In addition to Anna Tumarkin's extraordinary biography, the exhibition focuses on the beginning of women's studies in Bern, the groundbreaking role of pioneering women from Eastern Europe and shows the hurdles that women had to overcome in science. Several historical dynamics can be seen in this chapter of Bern's university history: on the one hand, education as a history of emancipation and, on the other, migration and internationalization as the innovative potential of a cosmopolitan university.

More informationen: https://tumarkin.unibe.ch/ausstellung/index_ger.html

Magazine uniFOKUS

Women in Science

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS focuses on one specialist area from different points of view. Current focus topic: Women in Science

Subscribe to uniFOKUS magazineSubscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.