History of science

Why science excluded women

Women were excluded from science for a long time. What were the reasons? What has changed since then, what still needs to be done? The historian Brigitte Studer, the gender researcher Andrea Zimmermann and the philosopher of science Julie Jebeile take stock.

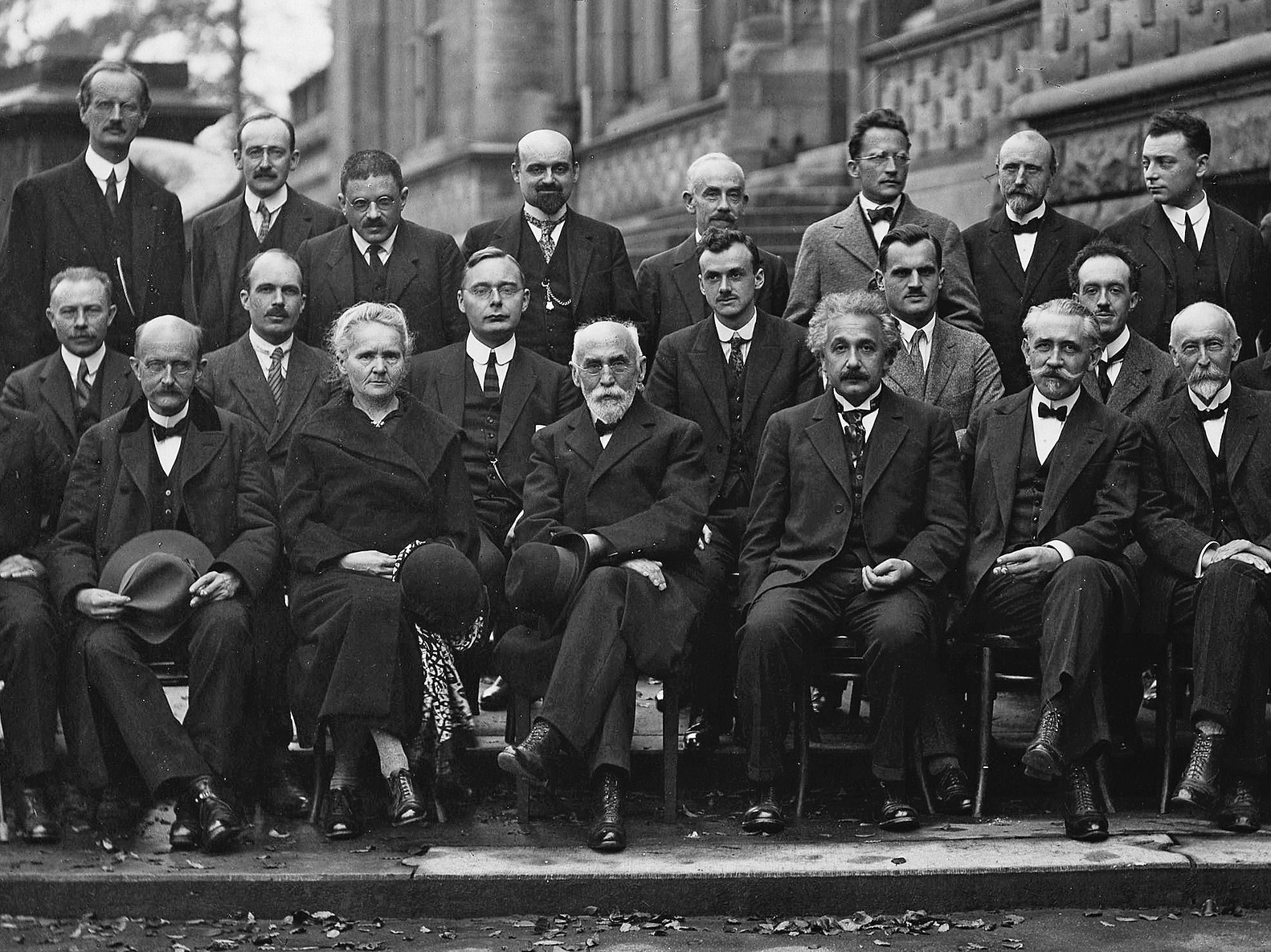

Let’s put it to the test: How does artificial intelligence view a scientist, a professor or a researcher? The generated images will mainly show (amazingly good-looking) men. Western men, of course, but that would be the subject of another text. The result can be explained by the database, i.e. by the “role models” with which the models were trained. In this respect, it can certainly be interpreted as a collective subconscious, as a reservoir of “our” conception of the world. And the idea that science is masculine is astonishingly old.

Monastic cultures as the origin of masculine science

In his immensely readable book “A World Without Women”, the historian of science and technology David F. Noble explores the origins of the “men’s alliance” that is science – he found them in the monastic cultures of the early days and the Middle Ages. Historian Suzanne Wemple took the same line: “One can only speculate what would have happened if the independent forms of female monasticism had been able to unfold freely, what kind of creativity would have emanated from the women’s communities if their members had not been isolated from the mainstream of religious, political and intellectual life.”

“Arguments against women’s competence have proliferated over the centuries, libraries could be filled with them.”

Brigitte Studer

Which leads us directly to Kant and to the Enlightenment ideal: That it does not matter who thinks, but only that one thinks, methodically correctly and with the audacity to question old dogmas. Sapere aude! Have the courage to use your own mind. You could have understood that from a feminist perspective. In practice, however, the emancipatory principle of the Enlightenment aimed at shifts in power among men. Away from the Church, toward newly emerging academic structures.

Enlightenment as an unfinished promise?

“Feminists have always been preoccupied with this: Is the continued exclusion of women ultimately an unfulfilled promise of the Enlightenment?” says Brigitte Studer, emeritus professor of Swiss and contemporary general history. In other words: Is the basic feminist attitude rather critical of the Enlightenment or, on the contrary, does the Enlightenment need something like an update, would it just have to be thought through to its logical conclusion?

Women as deformations according to Aristotle

If we put together the corresponding chauvinisms and stereotypes, then it becomes immediately clear that there is something completely wrong with the Western philosophical understanding at this neuralgic point. Kant, for example, said that women in relation to science have no “architectural” mind, because it is obscured by the “passions”. The most influential idea that women are best seen as natural deformations or imperfect men goes back to Aristotle (a cornerstone of scientific thought). Following this logic, it was easy to deny them the very qualities that were considered necessary to gain access to power circles.

Brigitte Studer names, for example, perseverance, but also the ability to think in an abstract or “reasonable” way. “Arguments against women’s competence have proliferated over the centuries, libraries could be filled with them.”

Such devaluations were, of course, not limited to science; as is so often the case, science simply reflects general societal trends in its values.

Subscribe to the uniAKTUELL newsletter

Discover stories about the research at the University of Bern and the people behind it.

The spark from heaven is reserved for men

And the stereotypes were rampant not only among men, but also among women: In her memoirs, Mary Somerville, one of the rare exceptional figures who were allowed to shine in the field of research as early as the 19th century, writes: “I have perseverance and intelligence, but no genius. This celestial spark is not granted to [our] race, we are of the earth, earthly – God knows whether we will be given higher powers in another existence; in this one, independent scientific genius is hopeless.” A lot has changed since then, but such hopelessness still persists. An example of this is the Swiss Chemical Society Paracelsus Prize, which is awarded every two years for an internationally outstanding lifetime achievement in the field of chemical research. Award winners so far: 32, of whom women: 0.

1780–1872

Mary Somerville

was a Scottish astronomer and mathematician who was called the “Queen of Science”. Somerville was best known as a science writer. The term “scentist“ was first used in a review of a book she wrote in 1834.

The genius myth as an obstacle

The genius myth is one of the defining stereotypes that gender researcher Andrea Zimmermann blames for the persistent discrimination against women in science. “Scientific culture still celebrates this image: A researcher has no social connections; he dedicates himself entirely to his research, driven by an inner compulsion.” This is not compatible with the social reality of women, even today (see article "Science and family: New ways of making them compatible"). Speaking of social reality: When women got lost in science, then without exception those of better standing.

This also applied to the “liberal island” of Switzerland, as Studer explains. Women were able to study at Swiss universities relatively early on, although there were major differences between the cantons. Studer attributes this not only to liberalism in Switzerland, but also to a certain pragmatism on the part of the university staff: For many lecturers, the foreign, mostly wealthy female students were a welcome opportunity to supplement their college fees, which accounted for a large part of their income. At the same time, the mostly Russian female students from good homes were treated with suspicion, as they often brought with them militant political ideas (see article "The history of women at the University of Bern").

Female students now in the majority

One thing is also clear: Access to studies was not the only obstacle put in women’s way. Even though studying law had long been a matter of course for women, it took a long struggle – until 1923 – before they were also admitted to the bar. This is because only those who had active citizenship rights (i.e. the right to vote) were allowed to work as a lawyer. Historically, Studer sees medicine as the gateway to professions with an academic background, as stereotypes tended to play in favor of women. The fact that these entrance gates, when they finally opened, were and are actively used can be seen in plain figures: In most countries it is now the case that more women study than men, with Switzerland toward the bottom of the scale ranking at 50.5% (for figures on the University of Bern, see articles "An inclusive view benefits everyone" and "Proportion of women at the University of Bern" ).

1897–1967

Johanna Gabriele Ottilie «Tilly» Edinger

was a paleontologist and founder of paleoneurology, which studies fossil brains. As a woman and a Jew, Edinger was doubly marginalized. For a long time, she underestimated the danger to life in Germany. In 1939, she fled to the United States, where she was accepted at Harvard University.

But: The stereotypes persist. As recently as 2005, Lawrence Summers, then Rector of Harvard University, caused a scandal when, in a speech, he sought out scientifically veiled reasons for the under-representation of women in leadership positions. The reasons are no longer as crude as they were in the late 19th century, when enthusiastic physiologists weighed brains and finally found the old prejudices confirmed: On average, women’s brains are about ten percent lighter than men’s brains.

“Being a scientist is balancing stereotypes.”

Andrea Zimmermann

But it is still easy to go astray if you ask the question, which is probably wrong in the first place, of whether “women think differently than men.”. Although studies show different competencies in certain fields, the data available is sparse at best, and the dilemma of how many of the differences can be attributed to socialization, such as unequal encouragement in school, cannot be resolved anyway.

Diversity of perspectives improves research

So what would it mean to ask whether we need a more “feminine” science? How do you avoid the pitfalls of essentialist thinking? The simple division “male equals rational, female equals empathetic” is certainly not helpful. Or as Zimmermann describes it: “Being a scientist is balancing stereotypes” – don’t be too masculine, don’t be too feminine.

Magazine uniFOKUS

Women in Science

This article first appeared in uniFOKUS, the University of Bern print magazine. Four times a year, uniFOKUS focuses on one specialist area from different points of view. Current focus topic: Women in Science

Subscribe to uniFOKUS magazineThe question posed at the beginning of the discussion of what creativity we could have had in research had science for a long time not remained so exclusively a masculine affair still keeps us thinking. The philosopher of science has a background in physics and is sure that science will change if “socially less privileged groups” are involved – by which she explicitly means not only women, but also people from non-Western cultures. In this way, Jebeile wants to change the perspective: towards a method of research that explicitly pays attention to power structures. Such an approach takes into account how scientific knowledge is associated with injustice.

1938–2011

Lynn Margulis

was a biologist and co-founder of the Gaia hypothesis. Margulis became famous for her theory of endosymbiosis, according to which evolutionary leaps occur when microorganisms merge into more developed life forms. Margulis’ theory can be found in every textbook on evolutionary biology today, but was not taken seriously by male colleagues for a long time. The underlying paper was rejected around 15 times prior to publication.

For example, Jebeile investigates how climate models can be created, focusing not only on the “bare” numbers, but also on the underlying premises. Who is behind the model, what interests are there, does the scientific discourse run along (research) political lines of power? There is a trend toward increasingly computationally intensive, finer-resolution models, represented by a relatively small group of powerful climate scientists with a mathematical-physical background. “Other researchers prefer to work toward an approach that is based on the people on the ground and their observations.”

Old stereotypes, repackaged

Which approach is more correct or relevant cannot simply be decided objectively, which is why Jebeile argues for a variety of perspectives. Because now we actually know: After all, science is not “neutral”, because there is often no one, best way to solve a problem. A woman’s view in particular can help to understand this, not because she is a woman, but because she belongs to a discriminated group.

“Science is not 'neutral', because there is often no one, best way to solve a problem.”

Julie Jebeile

Jebeile is convinced that this power-sensitive view is needed more than ever, also in other disciplines. Research and, above all, technology are intervening ever deeper into social processes, the keyword being AI. Is it a strange coincidence or is it part of the same old pattern when its creators (men, especially) at the same time complain that corporate culture has become too “feminine” and the necessary “masculine energy” is being suppressed (Quote from Mark Zuckerberg, CEO Meta) with valuable traits such as “aggression” being abandoned? Anyone who thought that we had finally left the old stereotypes behind us is certainly being proven wrong at the moment.

Contacts:

Prof. em. Dr. Brigitte Studer brigitte.studer@unibe.ch

Dr. Andrea Zimmermann andrea.zimmermann@unibe.ch

Prof. Dr. Julie Jebeile julie.jebeile@unibe.ch